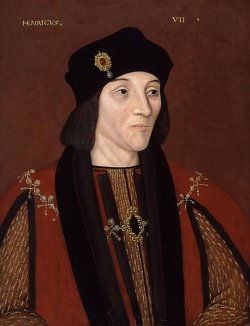

King Henry VII

Born: January 28, 1457

Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, Wales

Reign: August 22, 1485 - April 21, 1509 (24 years)

Died: April 21, 1509

Sheen, Surrey, England (Age 52)

Biography

Henry Tudor was born the only child of Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond (who died two months before his son’s birth) and his wife, Lady Margaret Beaufort, a girl of only thirteen. Though no one could have possibly anticipated Henry’s future rise to the throne of England, he did have a number of royal connections that are important to explain at this point given how important they would become later on. He was a nephew of King Henry VI, being that his father was a half-brother of the Lancastrian monarch, and Henry’s paternal grandmother was Isabella of Valois, the widow of Henry V and a daughter of the mad King Charles VI of France. In addition, Henry’s mother Margaret was a great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt, the third surviving son of Edward III, giving him a distant claim to the throne. The claim was a weak one, considering the fact that it was through a female, and a Beaufort female at that. Though John of Gaunt’s Beaufort children had been legitimized when he finally married their mother, Katherine Swynford (his long-time mistress), in 1396, King Henry IV, Gaunt’s legitimate son, later declared that, as a stipulation of their legitimization, the Beauforts were to be excluded from the royal succession. It can be argued though, that the house of York ultimately derived their superior claim to the throne over the house of Lancaster through a female line (and twice over at that) and the exclusion act against the Beauforts could easily be reversed through an act of parliament. But any claim Henry had to the throne at this point was meaningless and far-fetched, considering the fact that there were still a number of male-line Plantagenets alive, including Henry VI, his son Edward and the Duke of York and his four sons, three of whom would go on to have sons of their own. It was only when the remaining Plantagenets had virtually destroyed themselves in the Wars of the Roses and in Richard III’s violent usurpation of the throne that Henry’s distant claim would gain any substance.

Henry spent the first years of his life undoubtedly living in comfortable conditions with his mother (and nominally, his uncle Jasper, Earl of Pembroke) on their lands in Wales. When Edward IV took the throne in 1461 though, Henry was taken from his mother and uncle and made a ward of Lord William Herbert, a powerful and influential Welshman, in the service of the new Yorkist king. It is believed that Henry was being brought up to ultimately marry Herbert’s daughter. There is no evidence at all which demonstrates that Henry led anything less than a good life while under Herbert’s custody and, after Herbert was executed following his defeat at the Battle of Edgcote (at the hands of the Earl of Warwick and the king’s brother Clarence), he remained within his household.

The year following Herbert’s execution, the Lancastrians gained back power, chasing away Edward IV and his Yorkist allies, and Henry was reunited with his mother and his uncle Jasper. It is believed that, during this brief Lancastrian “readeption,” Henry met his uncle, Henry VI, for the first and only time, and the king promised good things for the youth. Unfortunately, the Lancastrian triumph would be very short-lived and Edward IV soon returned to take back his kingdom. By May 1471, all legitimate male members of the house of Lancaster were dead, including Henry VI himself. This meant that Henry’s mother Margaret was the sole remaining member of the fallen house, making her son the most likely candidate to the throne for the Lancastrian cause. Edward IV was well aware of this fact, and would have loved to have gained possession of Henry, but luckily, Henry and Jasper were able to make their escape from Wales. It is believed that they originally intended to travel to France where they would seek the protection of King Louis XI. But, the winds blew them further west to Brittany, where they were happily taken in by Francis II, the duchy’s duke.

For the next twelve years, Henry and Jasper lived in relative comfort within Duke Francis’s dominions and were treated well enough for men of their social position. Edward IV made repeated attempts to secure their persons, offering Francis lavish gifts and attempting to convince the duke that he meant them no harm and actually intended on marrying Henry to one of his own daughters (ironically, this is what would ultimately happen). On one occasion, Francis was actually fully set on returning Henry to England, but was convinced that only death would await him there. Not wanting to lose a valuable bargaining took, or to see an innocent man put to death, Francis continued his protection of Henry and his uncle, but struck a deal with Edward IV that they would be kept in close custody and would not be given any opportunities to cause trouble for Edward’s regime. Edward IV seemed content with this and, as time went by, worried less and less about his obscure dynastic rival.

Henry’s fortunes began their unexpected rise in April 1483 when Edward IV suddenly died. The story that follows is well known. Edward IV’s younger brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, went on to usurp the throne from his nephew, Edward V, and proceeded to eliminate anyone who stood in his way to power, including, most likely, his two young nephews. With Edward IV and his two sons gone, Henry was transformed from an unknown exile to a viable alternative to a despotic leader. Richard III, though a competent and intelligent man, had played his cards wrong, and the violent and tyrannous means in which he employed to gain the throne would gain him widespread hatred. Henry and his small, but slowly expanding, band of followers knew that this would be the time to capitalize. It comes as no surprise that, very shortly after his coronation, Richard III attempted to cajole Duke Francis into delivering Henry into his hands, but to no avail. Francis knew very well that, if Richard III was capable of murdering his own nephews, it can only be assumed that a similar fate would await Henry.

Henry’s first opportunity to seized the throne came in the fall of 1483 when rebellions against Richard III were staged in various areas throughout England. Soon after, the Duke of Buckingham, once Richard III’s staunchest supporter, joined the rebellion. Henry’s mother Margaret, Queen Elizabeth (the widow of Edward IV), Bishop John Morton of Ely and various others were all part of a plot in which the main goal seems to have been to replace Richard III with Henry, who would then go on to marry Edward IV’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth, to unify the houses of Lancaster and York. Duke Francis provided Henry with several thousand soldiers and a number of ships for his proposed invasion of England, and Henry duly set out to attempt to win the kingdom from Richard the usurper. Unfortunately, this rebellion was destined for failure. Buckingham was deserted by his men and shortly after captured and executed. Henry did not have much luck at sea either, as storms scattered his fleet, causing only his ship and a few others to land safely in England. A group of Ricardian loyalists tried to dupe Henry into believing they were Buckingham’s men to gain custody of him, but Henry suspected something was awry and departed back to the continent to fight another day. Though Richard III had won this particular battle, it became increasingly clear that he had by no means won the war.

After the recent threat against his regime, Richard III more aggressively pursued his entreaties to Duke Francis to gain possession of Henry’s person by offering to give him military assistance in the defense of Brittany against French hostility. With Brittany being the last independent duchy with France, there was the real possibility that it would be absorbed into France (just as Burgundy had been several years earlier) if Duke Francis died without male issue. Therefore, Francis needed all the help he could get, but still refused to outright give up his valuable guest. However, at a point when the duke was bedridden, Richard III cut a deal with Brittany’s treasurer, one Peter Landois, who agreed to give up Henry in exchange for a small army of English archers. Henry somehow got wind of this plot and staged a dramatic escape into France to seek the protection of King Charles VIII. When Duke Francis heard of his treasurer’s betrayal, he was infuriated and gave Henry safe conduct to depart his duchy. Henry, whose personal retinue was gradually swelling and now included such competent men as John de Vere, Earl of Oxford (a loyal Lancastrian), was received in France fairly warmly by Charles VIII and began making preparations for his second invasion of England. Meanwhile, events in England continued to deteriorate for Richard III. The king lost both his wife and son, making his position on the throne even more precarious, and, at the same time, was accused of murdering his wife in order to wed one of his own nieces. Clearly, Richard’s fortunes were on a steady decline.

With Richard III is such a weakened state, now was the perfect time for Henry to strike, and strike he did. In August 1485, Henry set out from France with a respectable army of French and Breton mercenaries, as well as a number of rebel Englishmen loyal to his cause. Landing in Milford Haven on the Welsh coast, Henry and his army swiftly marched across the entire length of Wales and into England, waiting for the inevitable conflict with the royal army. Though momentum seemed to be in Henry’s favor, he was at a distinct disadvantage when it came to military experience, given the fact that Henry himself had never once fought in a battle, while Richard III had been commanding armies since he was a teenager. The royal army and the rebel forces ultimately met at the market town of Bosworth on August 22, 1485. Details of the highly significant Battle of Bosworth are sparse and dependant on a number of different chronicles that are only semi-reliable at best. It is believed that the royal army was nearly double the size of Henry’s and Richard III indeed possessed a number of able commanders. However, a key factor in the battle was that two powerful noblemen, the Earl of Northumberland and Thomas Lord Stanley (the latter of whom was Henry’s stepfather), whom Richard was depending on, ultimately decided not to intervene on his part. Seeing that he was losing support, the king decided to go for broke and made a desperate last charge at Henry himself. Though Richard made a valiant effort and got so close to his nemesis that he actually cut down his standard-bearer, Sir William Brandon, it was at this point that the army of Sir William Stanley (brother to Lord Stanley) threw in their support for Henry and Richard III was subsequently unhorsed and killed. The king’s death decisively ended the battle in the rebels’ favor and on that day, Henry Tudor, the obscure Welsh exile who had spent the last fourteen years of his life away from home, was proclaimed King Henry VII of England.

Henry spent the months following his victory at Bosworth organizing his new regime and consolidating his power. All those who had been loyal to him were greatly rewarded by way of titles, grants of land and/or appointments to lucrative offices within the new government and steps were taken to establish Henry’s own personal household and finances. One event that occurred during this time period that is worthy of mention is Henry’s arrest and imprisonment in the tower of the fifteen-year-old Edward, Earl of Warwick. Warwick was the son of George, Duke of Clarence, the brother of Edward IV and Richard III who had been executed for treason in 1478, and was the last legitimate member of the house of York (and Plantagenet for that matter) in the male line. For this reason, Warwick had a highly legitimate claim to the throne and was therefore an immense threat to Henry’s security and had to be kept under an extremely close watch. Warwick would be a thorn in henrys’ side for the remainder of his (Warwick’s) life and later troublesome events in the reign would involve him in some way.

In the meantime though, Henry needed to concentrate on securely setting himself up as England’s new king. Two months after Bosworth, he was officially anointed and crowned king and his first parliament met the following month. In this parliament, it was established that Henry had a right to the throne both through royal descent (as the heir to Lancaster), as well as through conquest, and that the first day of his reign was August 21, 1485, the day before the Battle of Bosworth. The reason why this is significant is that Henry was now able to say that those who had fought against him at Bosworth were guilty of treason and therefore were to be attainted. A number of Richard III’s staunch supporters (including the late king himself) indeed suffered this fate, while others (who had rebelled against Richard III) had their attainders reversed. Lastly, Henry confirmed his intentions of marrying Edward IV’s daughter Elizabeth of York. After several months of hammering out certain details, the marriage duly took place in January 1486. Several months later, Henry faced what would be the first of several rebellions against his regime by remaining loyalist of the house of York. Francis, Viscount Lovell (a childhood friend of Richard III) and Humphrey and Thomas Stafford, all of whom had been sanctuary since Bosworth and all of whom had been attainted at the subsequent parliament, planned a small and unorganized rebellion against the new king which never really got off the ground. Henry acted swiftly and captured the Staffords (one of whom was executed) and Lovell was forced to go into hiding.

Henry received a more serious threat to his dynasty the following year when Lovell joined forces with John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, and the two men paraded around a young man named Lambert Simnel as a potential rival to the throne, claiming that he was Edward, Earl of Warwick. Lincoln, who had actually been treated respectably by Henry since his accession, was a nephew of Edward IV and Richard III, being a son of their sister Elizabeth, and was believed to have been named heir to the throne at one point by Richard III (after the death of the latter’s own son). Though the plot undoubtedly had a major flaw, being that the real Earl of Warwick was still in Henry’s custody and he need only produce him to the royal council (which he did) to show that Simnel was an imposter, it did receive some support. In Ireland, a place that possessed a good deal of Yorkist allegiance, Simnel was actually crowned (unofficially of course) as King Edward VI. Margaret of York, dowager Duchess of Burgundy and another sister of Edward IV and Richard III, provided Lincoln and Lovell with money and an army from the Low Countries. The rebels made their move in June 1487, invading England from Ireland with a rather ragtag army of mainly Irish and German mercenaries. Henry though, was well prepared and the royal army was able to defeat the rebels at the Battle of Stoke, in what is largely regarded to be the last official engagement in the Wars of the Roses. Lincoln and several other Yorkist commanders were killed in the battle, Lovell disappeared (never to be seen again) and Lambert Simnel was captured. Knowing that Simnel (a boy of only around ten) was a mere pawn of Lincoln’s ambitions, Henry treated him mercifully, giving him a job in the royal kitchen. Simnel would later be promoted to the king’s falconer and lived well into the reign of Henry VIII. Others involved in the rebellion were punished and Ireland was relatively easily convinced to swear allegiance to Henry, ending the second rebellion in two years for the young Tudor regime.

In the years after the Battle of Stoke, Henry attempted to work on his foreign alliances. He was put in a very awkward position when he was made to choose between aiding either France or Brittany, both of whom had aided him in taking the throne, and ended up staying up neutral. More importantly, Henry signed the Treaty of Medina del Campo with Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, which was ultimately to be sealed through a marriage between Henry’s son and heir, Prince Arthur, and a Spanish princess. In addition, the two countries were to join forces against their common enemy, France. The treaty, through drawn up and agreed to in early 1489, was not officially ratified by Henry until the fall of 1491.

By 1491, Henry was forced to focus his attentions on yet another pretender to his throne, this time in the form of a young man named Perkin Warbeck, who turned out to be nothing more than the son of the comptroller of Tournai. Warbeck claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the two sons of Edward IV, both of whom were long thought to have been dead, murdered by their uncle, Richard III. Though Henry was not forced to deal with any full-scale battles during Warbeck’s rebellion, the king was at a disadvantage because he was not able to simply able to produce either of the so-called “princes in the tower,” as he was able to do with Warwick in 1487, being that that he himself did not know what their fate was. For this reason, the Warbeck rebellion was much more complicated and drawn out. Like Simnel, Warbeck was able to receive nominal support from the Irish, Charles VIII of France and his “aunt,” Mary of Burgundy, the latter of whom readily recognized him as her nephew. Henry, however, kept a close eye on the pretender and made sure that none of his support ever really materialized. The whole situation was an inconvenience for the king though, being that Ferdinand and Isabella refused to go any further with the marriage alliance between the two countries until Henry’s throne was completely secure, which it would not be as long as Warbeck was causing trouble. Not finding any great amount of support in Ireland or on the continent, Warbeck decided to try his luck in Scotland and was welcomed into the country by King James IV in 1495. This was a grand opportunity for the young and ambitious king to humiliate Henry. It appears that James IV, at least to an extent, believed that Warbeck was who he said he was, and even went so far as to marry him to a kinswoman of his. The following year, Warbeck and the Scots actually invaded England, though they accomplished little and quickly returned back to Scotland.

In order to fund the money to defend England from Warbeck’s intrigues, Henry was forced to raise taxes significantly, causing a rebellion to break out in the already impoverished duchy of Cornwall. Again though, Henry acted quickly and decisively and was easily able to defeat the rebels at the Battle of Blackheath in mid-1497. With the Cornish rebellion at an end, Henry turned his sights to peace talks with James IV so as to prevent him from providing any more aid to Warbeck. It seems that James was already growing weary of the pretender by this point and it did not take much convincing for him to agree to the Treaty of Ayton (which would not officially go into effect until 1502), which was to be sealed through the marriage of James IV and Henry’s eldest daughter, Margaret. With England and Scotland now at peace, Warbeck was forced to flee to Ireland to find assistance for his now seemingly hopeless cause, but found none forthcoming. In a last desperate attempt at success, Warbeck invaded England via Cornwall (obviously hoping to capitalize on the recent disaffection with Henry’s government in the region) with a pathetically small army. Though Warbeck did gain some followers, his success was minimal and he was ultimately deserted and captured.

Surprisingly, Henry treated the pretender mercifully and respectably, just as he had done with Simnel, and welcomed him into his court. But, unlike Simnel, Warbeck was not to be as appreciative and the following year, he fled from royal custody. He was quickly recaptured though, and this time put under harsher restraint in the tower. Finally, in late 1499, Warbeck attempted to escape once more, this time in league with the Earl of Warwick, whom he was lodged close to in the tower. Many historians will claim that Henry deliberately put the two men close together, knowing that they would join forces, in a plot to finally rid himself of the last male Plantagenet and the biggest threat to his dynasty. It will never be known if this is true, but Henry did not plan on showing any mercy this time, and both Warbeck and Warwick were convicted of treason and executed.

After the executions of Warbeck and Warwick, Henry’s throne was most certainly more secure and the marriage alliance with Spain was able to go forward. Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon, youngest daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, were finally married in late 1502. Unfortunately, Arthur, who had always been a sickly child, died the following spring at the age of fifteen. Negotiations were opened almost immediately for Catherine to marry Henry’s only remaining son, Prince Henry, a marriage that would ultimately bring about drastic changes within England. The year following Arthur’s death, Henry lost his beloved wife, Elizabeth, who passed away during childbirth. Henry did face some other smaller threats to his throne, mainly from the de la Poles, the younger brothers of the Earl of Lincoln who had perished at Stoke. In 1502, Sir James Tyrrell, a former supporter of Richard III who had been taken into favor by Henry, was executed for aiding and abetting the actions of Edmund de la Pole. Before he died, Tyrrell confessed to the murder of the princes in the tower. It is quite possible that Tyrrell was being honest, considering he had nothing to lose at the time, but certain historians will argue that it was a forced confession to further secure Henry’s weakened dynastic position after the death of Prince Arthur.

The deaths of his son and wife in successive years, combined with the fact that he already seemed to be suffering from the sickness that would ultimately kill him, seem to have brought about a sharp change in Henry. For the remainder of his life and reign he continued to grow increasingly bitter, senile and miserly. Henry spent his last years attempting to ensure that his dynasty would continue smoothly after his death. He was heavily active in the hostile politics of the continent and contemplated, on various occasions, of forming alliances with Spain, France and the Holy Roman Empire. A major issue in this time period was the securing of the marriage between Prince Henry and Catherine of Aragon, his brother’s widow, in addition to a second marriage for King Henry himself. The latter marriage would never happen and the former became a prolonged affair that would not end up occurring until two months after Henry’s death. In the meantime, Catherine remained in England and was treated very harshly by her former father-in-law, most likely as punishment for her father Ferdinand’s refusal to pay a large portion of her promised dowry, and was kept in a state of near-poverty. Even Prince Henry himself was not safe from his father’s greedy and cruel behavior and was certainly kept under close lock and key, being that he was the only remaining male heir of the house of Tudor. Up until the end though, the elder Henry was respected (if also hated and feared) by his people and fellow monarchs. Henry VII died on April 21, 1509 at the age of fifty-two. He was succeeded on the throne by his only remaining son as King Henry VIII.

Assessment and Analysis

Henry VII has always been looked at as somewhat of an enigma, even in his own time. The fact that, as a man who had only visited England once in his lifetime, he was able to take a dubious and obscure claim to the throne and make himself King of England shows that he was an ambitious and opportunistic man who knew exactly when to take decisive action. Henry knew exactly when to run and hide and when to charge headfirst into battle. He knew that he would stand no chance of gaining the throne from a man such as Edward IV but knew that he would be able to take advantage of the tyrannous actions of Richard III. The Battle of Bosworth, which put Henry in power, continues to be one of the most significant events in English history. Henry’s victory ushered in a new era with England, putting a new dynasty on the throne for the first time since 1154. It also marked the unofficial end of the Middle Ages. During Henry’s reign, the world experienced the artistic and literary works of men such as Leonardo da Vinci, Niccolo Machiavelli and Desiderius Erasmus which ushered in a new humanist way of thought previously unheard of. Additionally, the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot, the latter of whom Henry personally funded, proved to all that there was more to the world beyond the Strait of Gibraltar.

Henry’s own style of kingship had significant differences from his predecessors. Though he showed that he was ready for battle if the need arose, made clear by his victories at Bosworth, Stoke and other various rebellions, he preferred mercy and diplomacy over death and violence. Henry showed unprecedented mercy when he fully pardoned Lambert Simnel and even treated Perkin Warbeck with kindness despite all the trouble he had caused. It was only when a man heinously betrayed Henry that he showed that he had a mean streak to him. Warbeck had rejected his mercy and paid the ultimate price for it, as did Sir James Tyrrell. Sir William Stanley, the man who had greatly aided Henry at Bosworth, was another example when he was executed for his implication in the Perkin Warbeck conspiracy. The Earl of Warwick seems to have been Henry’s only real exception (discounting Richard III’s former henchmen after Bosworth), but Henry knew his dynasty would never be safe while a male Plantagenet lived, and was probably reluctant to execute Warwick, who seems to have suffered from some sort of mental deficiency and was really guilty of nothing more than possessing Yorkist blood.

It was indeed a new era in English politics that Henry VII presided over. The feudal system was slowly but surely waning and the merchant classes and parliament were rapidly gaining more influence in government and society. Henry was able to neutralize the nobility by keeping them under strict financial restraint, yet rewarding them when they deserved to be rewarded. This was an entirely different philosophy from past monarchs such as Edward III and Henry V, who distracted their ambitious magnates by concentrating their attentions against foreign enemies, mainly the French and the Scots. Though Henry’s ill health and paranoia began to get the best of him in his last few years, just as they would to an even greater extent with his son and successor, it would be difficult to make the case that he was not a successful king and even more difficult to say that he was unique. All in all, it must be agreed that Henry took a kingdom in crisis away from a despotic child-killer and molded it into a prosperous center for the arts and humanities. Henry VIII was most certainly lucky to succeed a man like his father, Henry VII.

Further ReadingBeavan, Bryan. Henry VII: The First Tudor King

Cavill, Paul. The English Parliaments of Henry VII, 1485-1504

Chrimes, S. B. Henry VII

Cunningham, Sea. Henry VII

Grant, Alexander. Henry VII

Lockyer, Roger and Andrew Thrush. Henry VII

Simons, Eric N. Henry VII: The First Tudor King

Storey, R. L. The Reign of Henry VII

Williams, Charles. Henry VII

Williams, Neville. The Life and Times of Henry VII