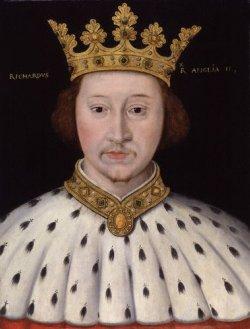

King Richard II

Born: January 6, 1367

Bordeaux, France

Reign: June 22, 1377- September 29, 1399 (22 years)

Died: February 14, 1400

Pontefract, West Yorkshire, England (Age 33)

Biography

Prince Richard of Bordeaux was born January 6, 1367, the second, but only surviving child, of Edward, Prince of Wales (also known as the Black Prince and the eldest son and heir of King Edward III) and his wife, Joan of Kent, in Bordeaux, Gascony, where the Black Prince was serving at the time. At the age of four, Richard became second in line to the throne upon the death of his elder brother, Edward of Angouleme, and heir apparent when his father, the Black Prince, died five years later (1376). Richard was dubbed a Knight of the Garter by his grandfather only months before the old king died on June 21, 1377. With the death of Edward III, Richard ascended the throne as King Richard II at the young age of ten.

Some sort of arrangement had to be made when it came to governing the country, considering the fact that the king was well under age. In the case of Henry III (who became king at the age of nine) in the previous century, a regent, William Marshal, was given the task of controlling the kingdom. The most obvious choice for the position during Richard’s was John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, third surviving son of Edward III and therefore the king’s uncle. Many contemporaries, however, were concerned with the fact that John was extremely unpopular with the commons, in addition to not wanting him to become too powerful. Therefore, Richar was deemed fit to govern and a series of councils were set up to conduct business in the king’s name for the next three years. When the first of these councils met, not only was John left out, but also the king’s other remaining uncles, Edmund of Langley and Thomas of Woodstock, the Earls of Cambridge and Buckingham respectively. Though John had no official title in Richard’s government, he was to remain a leading and influential political figure for nearly the entire reign, though he and the king would not be without their differences.

A lingering problem from the last reign was the situation in France. The Treaty of Bruges expired a few days after the death of Edward III and the French pounced on the opportunity of gaining back the rest of their territories while England was under the rule of a ten-year-old boy. Under the leadership of King Charles V, the French proceeded to stage attacks on English port cities and sent armies in English territories in Brittany and Gascony. Though a French siege of Calais turned out to be unsuccessful, the French did gain even more ground on winning back Gascony, reducing English possessions in the duchy to very small coastal areas around Bayonne and Bordeaux. The English, under the nominal command of men such as John of Gaunt and Thomas of Woodstock, did invade France, but achieved practically nothing and were forced to return home empty-handed. In addition, the English made a number of pointless alliances that would only end up costing them more money.

To pay for all these fruitless endeavors, parliaments had to be called and taxes had to be levied. For the most part, the commons were well aware that large amounts of money were needed for the defense of England and its continental territories and for continual military expeditions which could gain further ground against the French. Therefore, they usually granted freely the money that the royal exchequer required to keep up with these costs. But, they expected results. In 1380, after being granted a generous subsidy from the commons, a larger English army then on the previous campaigns, under the command of Thomas of Woodstock, departed for France. The army failed to do the exact same thing it had failed to do in the previous expeditions: to bring the French onto the battlefield. Woodstock marched with the army all the way from Calais into Brittany, accomplishing very little along the way. By this point, Woodstock was out of money and another parliament had to be called to ask for more funds. In this parliament (which was called in very soon after the last one had ended), yet another poll tax, the third of its kind, was approved by the commons. Meanwhile, the English achieved a significant victory when Charles V died and was replaced by his eldest son, Charles VI (like Richard II, a minor), but lost a valuable ally when John of Brittany informed them he was dropping his support for the English cause. Woodstock was forced to conclude a humiliating truce with the French and return home. The combination of brutal and unfair taxation and expensive military campaigns that accomplished nothing would prove to be a lethal combination.

The third and final poll tax that was imposed on the English people was particularly devastating because, unlike the previous two taxes, it was a flat one and it was the poor who were affected worst of all. Therefore, it is no surprise that the commons were unable, or unwilling to pay it, and when the time came for the tax to be collected, tax collectors were chased away. These smaller uprising developed into two major rebellions in Kent and Essex, which ultimately came together and marched on London to attain justice against the king’s evil advisors (but not the king himself) for their hardships. At the head of the rebel faction was the charismatic Walter (or Wat) Tyler, a local tradesman. As the rebels approached London, Richard agreed to meet with them at Blackheath. Since the king would have been in danger if he met with the rebels face to face, he communicated with them while on a barge in the Thames. The rebels demanded that all of Richard’s hated councilors be executed, including his uncle, John of Gaunt. It was impossible for the king to agree to these demands and the rebellion continued.

The rebels gained access to London and caused massive destruction. Houses of many lawyers were destroyed, prisoners were freed from local jails, foreigners were slaughtered and John of Gaunt’s exquisite palace, the Savoy, was burnt to the ground. Luckily, John himself was in Scotland at the time. As the chaos continued, Richard and his court were forced to take refuge in the tower. Knowing that something had to be done, Richard agreed to meet with the rebels personally at Mile End and agree to their demands, which involved the abolition of serfdom and the right for them to personally execute the men they believed to be traitors. The king replied with a generic comment that their demands would be considered and that justice would be brought to any man who, by law, was deemed a traitor. Incorrectly, the rebels thought this meant that they may take the law into their own hands and immediately made for the tower of London where they forced entry. They seized two of Richard’s most loathed advisors, Archbishop Simon Sudbury of Canterbury, the chancellor, and Sir Robert Hales, the treasurer, and had them beheaded in brutal fashion like common criminals. After this disastrous event, the king agreed to meet with the rebels a third and final time, at Smithfield.

This time, the rebel leader, Wat Tyler, met with the king personally. As the king was agreeing to all the previous demands the rebels had made to him, certain men in the royal party felt that Tyler was being overly familiar with his king and an altercation broke out. Through there are many different stories as to what happened in various chronicles, it seems that William Walworth, Lord Mayor of London, stabbed Tyler, mortally wounding him, and the rebel leader was finished off by other members of the royal party. With Tyler’s death, the remaining rebels were already beginning to dissipate. After the main rebellion in London was subdued, all smaller uprisings throughout the country quickly followed. There were a number of rebel leaders executed, but most of the lesser rebels were pardoned. Despite the king’s promises to the rebels in their several meetings, no real reform took place (though the poll tax was not levied). All in all, though, the Peasant’s Revolt showed that the fourteen-year-old Richard was able to stand tall during a crisis and use his words to help accomplish his goals. Broken accords aside, the king’s handling of the revolt showed promise for the future.

After the Peasant’s Revolt was finally subdued, attention was turned, once again, to finding a suitable marriage for King Richard. As a result of the Great Papal Schism, in which the English supported Pope Urban VI over his French-endorsed rival, Clement VII, England was looking for a marriage that would create more allies against the French. After several years of searching, it was agreed that Richard would marry Anne of Bohemia, daughter of the late Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV, and sister to King Wenzel of Bohemia. The marriage and Anne’s coronation duly took place in January 1382. Though Richard loved his new bride dearly, the marriage would ultimately not do anything to help England against France or gain them any diplomatic bargaining power at all. Also during this period, the English suffered a number of military failures, under various commanders, in places such as Portugal and Flanders. A lack of funds for the expeditions certainly played a factor in these debacles and the expedition to Portugal was a part of John of Gaunt’s long-running scheme to become King of Castile through right of his wife, Constance, a daughter of the deposed (and murdered) king, Pedro the cruel.

During the following years, the king gradually came of age and moved closer to reaching his majority reign. It was also during this period that he began to come under the influence of a small group of courtiers that were to greedily consume all of his attentions. This group consisted of three primary figures: Sir Simon Burley, the king’s tutor since he was a young child; Michael de la Pole, the king’s chancellor and Earl of Suffolk after 1385; and Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, whom Richard would ultimately upgrade to Marquis and, soon after, Duke of Ireland. Relations between Richard and his uncle John were also tense during this time and it was rumored both that John was attempting to have Richard killed and Richard’s followers were attempting to have John murdered. Disgusted by what was going on at court and emboldened by a Portuguese victory over the usurping Castilian dynasty he was attempting to overthrow, it was no surprise that John took the opportunity to pursue his claim to the Castilian throne and departed England in July 1386, where he would remain for the next three years.

Without the firm hand of John of Gaunt to keep tensions under control, politics in England, both foreign and domestic, became extremely volatile. Knowing that their Castilian allies were under attack by Gaunt, the French began to muster a large army and meant to conduct a full-scale invasion of England. Preparations, of course, needed to be made and that meant that parliament needed to be called so that a tax could be levied for the defense of the realm. At the so-called Wonderful Parliament, the Earl of Suffolk, the royal chancellor, seemed to have overstepped his boundaries when he asked for an abnormally large tax to be subjected on the commons. The proposal immediately met with widespread objections and the calling for Suffolk’s dismissal. Richard, under pressure from his uncle, Thomas of Woodstock, now Duke of Gloucester, and his political allies, had no choice but to give in and dismissed Suffolk from office. Parliament then further pursued the accusations against the earl until it was decided that he was to be officially impeached from office, which he ultimately was. Richard was undoubtedly shaken by this opposition to his power and it must have reminded him of the situation involving his great-grandfather, Edward II, who was deposed for his favoring of a select few courtiers. For the time being, Gloucester and his allies were to control the day to day comings and goings within the country in the form of a council, which was to last for the duration of a year. The council then set about revising the expenses of the kingdom and the king’s personal household, in addition to attempting to limit the power of the king’s favorites, men such as Burley and de Vere.

The anti-royal faction that Gloucester had formed, which also included the Earls of Arundel and Warwick, came to be known as the Lords Appellant, because the lords were only trying to appeal to the king to govern the realm more effectively and not surround himself with bad counselors. Later in 1387, the Appellants were joined by Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham, and Henry Bolingbroke, eldest son and heir of John of Gaunt. All five men had some sort of quarrel with the king and his favorites that drew them together. Richard, unhappy with this encroachment of his royal authority, bided his time and consolidated his power, and once the Appellants’ power in the council was about to expire, Richard attempted to make a move to take power from them. The Appellants got wind of the king’s plotting and prepared to make the first move. Upon hearing this, many of the king’s favorites, including Suffolk, fled the country. De Vere, however, decided to remain with Richard and mustered an army to fight for the royal cause. The Appellants retaliated with an army of their own and the two sides met at the brief and, for the most part, bloodless, Battle of Radcot Bridge. De Vere’s men were easily defeated by the Appellants and de Vere himself escaped and departed England.

After de Vere’s defeat, Richard had no choice but to, once again, give in the Appellants. At the appropriately named Merciless Parliament that proceeded Radcot Bridge, the Appellants were in firm control and moved against all the king’s favorites. Some chroniclers actually go so far as to state that the king was officially deposed for several days, but there is no real evidence to sustain this theory. Both Suffolk and de Vere had already fled, but were given death sentences nonetheless and ended up dying in their respective exiles. Several other of Richard’s favorites were executed, including Chief Justice of the King’s Bench Robert Tresilian and former Lord Mayor of London Nicholas Brembre, in addition to several judges who had once opposed the Appellants. A number of others were exiled, stripped of their lands or, in the case of clerics, their temporalities. In the eyes of many historians, however, the biggest event to happen during the Merciless Parliament was the execution of Richard’s tutor, Simon Burley. Despite a number of objections from those present at the parliament, including the two junior Appellants, Bolingbroke and Mowbray, and the king’s other uncle, Edmund of Langley (now Duke of York), Gloucester and Arundel insisted that the court needed to be cleansed completely of the men they felt had misled the king and Burley died at their command. It would not be inaccurate to believe that Burley’s execution led to the actions that Richard would, years later, take against the Appellants. All in all, the Appellants achieved their goals at the Merciless Parliament of cleansing the court of Richard’s despised favorites and humiliating the king himself, reducing him to a mere figurehead who existed only to act in their interests.

Now that they had gained power, the Appellants decided to renew interest in the war against France. Arundel led a naval force to the continent, but was unable to gain the support of any of the continental allies he had hoped to and the expedition ended in complete failure. Meanwhile, the Scots using their familiar strategy of taking advantage of England’s preoccupations with continental business, crossed the border and began devastating the northern counties. They were opposed by the English border lords Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, and his son, Henry “Hotspur” Percy. A the Battle of Otterburn, the Scots handed the English a decisive defeat and Hotspur was taken captive. The combination of this defeat and the lack of success in France (which resulted in high taxes) allowed Richard to play off the commons against the Appellants’ rule and gain back power. By this point, Richard’s political views had moderated (seemingly) and, with the return and assistance of John of Gaunt, he was able to gain a less tenuous hold on his kingdom. The Appellants were dissolved (with Mowbray and Bolingbroke being fully returned to royal favor), Richard declared himself of age to rule and a period of relative peace within English politics began.

During the years that followed, Richard gradually built up his power base. Not only did he make peace with John of Gaunt, who proved to be the most loyal supporter of the royal prerogative, but the king was also able to control parliament more effectively by rewarding a number of men who represented the commons, such as Sir John Bussy, Sir William Bagot and Sir Henry Green. In addition to these representatives of the commons, Richard also showed favor to several others of noble, or even royal, blood such as Sir William Scrope (later Earl of Wiltshire); Thomas and John Holland, Earls of Kent and Huntingdon respectively (and both half-brothers of the king; and Edward, Earl of Rutland (son and heir of the Duke of York and therefore a cousin of the king). All of these men would ultimately form Richard’s second group of hated favorites and a number of them would suffer the same fate as those that the king had earlier showed excessive favor to. Meanwhile, with the neutralizing and faithful presence of John of Gaunt to help guide the king, the first several years of Richard’s personal reign remained fairly uneventful. One of Richard’s fist priorities, after gaining back control from the Appellants, was to agree to a lasting peace with France. Richard was fully aware that it was the war on the continent, which had not been successful for many years, that was bleeding the exchequer dry and forcing the government to tax the commons into oblivion. With the French suffering from similar issues, it came as no surprise that the Treaty of Leulingham was willingly signed by both Richard and Charles VI (who by this point was beginning to suffer from a mental disorder that was to cripple him for the rest of his life).

The truce between England and France was continuously renewed but the issue of which areas were to be under English control and whether Aquitaine was to be held by the English in full sovereignty or as a vassal of the French king, requiring liege homage to be performed. Richard invested John of Gaunt with the duchy but even his political savvy was able to bring the situation in the duchy under firm control and it is believed that John’s failure in Aquitaine was one of the reasons for the falling out between him and the king by 1396. An opportunity opened up for more cordial relations between the two countries when Queen Anne died in June 1394. Richard had loved his wife dearly but their marriage was childless and the king was well aware that, if the direct line of the Plantagenet dynasty was to continue, he would need a son. After shopping around the continental market for potential brides, it was agreed that Richard would marry Isabella of Valois, the six-year-old daughter of Charles VI of France. Once the details of the marriage were settled, the two kings and their entourages met in the fall of 1396 in a luxurious ceremony at Ardres, near Calais, so that Richard could received his new bride. As a result of the marriage, a lengthy truce was agreed upon between the two sides.

In 1394, Richard became the first English king since King John in 1210 to travel to Ireland when he decided to lead a substantial force to the isle in an attempt to control the near chaotic situation that was occurring there. Though by no means the general his father and grandfather had been, Richard was able to achieve a remarkable amount of success in a place where so many other had failed miserably. By the time he left Ireland, Richard had forced a majority of the rebellious Irish lords, who had been living on their lands as virtual kings, thinking themselves free from English rule, into submission.

After eight solid years of domestic peace and political moderation within Richard’s government, many historians find the events that were to occur in 1397 to be strikingly bizarre. Without warning, Richard had the three senior Appellants, Gloucester, Arundel and Warwick, arrested and put on trial before parliament, just as they had done to him and his favorites in 1388. The reasons for Richard’s sudden aggressive behavior vary amongst the different chroniclers of the time and modern historians have added yet more theories over the years. It is true that the senior Appellants had become, for the most part, political non-entities since Richard began his majority rule and they no doubt harbored ill feelings towards the king and his growing group of new favorites. Therefore, it is not surprising that certain chroniclers claim that the Appellants were laying down a plot to depose the king. This, however, is fairly far-fetched and there is no real evidence whatsoever to give the claim substance. It is much more likely that Richard had simply been biding his time and building up his power base to the point where he felt strong enough to exact revenge on the men who had humiliated him in such a grave manner years earlier. Other contributing factors to Richard’s tyrannous behavior are the decline in the influence of John of Gaunt (and the king’s desire to show that he could rule firmly without his uncle’s assistance) and the death of Queen Anne three years prior. Many contemporaries claim that the latter event caused the king to slowly but surely become insane, until he exploded in an episode of violence, of which the arrest and trial of Appellants was the end result.

Gloucester was put into the custody of the former junior Appellant, Thomas Mowbray, at Calais, but Arundel and Warwick were immediately brought to trial at the parliament that followed their arrest. After the pardons that the Appellants had received at the Merciless Parliament were revoked, the king proceeded to destroy his enemies. Arundel, despite a spirited defense was convicted of treason and beheaded, while Warwick begged for his life and was spared, receiving a sentence of life exile on the Isle of Mann. Arundel’s brother Thomas, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was also exiled. When Gloucester’s presence was requested, it was announced that he was already dead. It is by no means clear as to what happened to the duke, but most chroniclers and historians alike have come to the conclusion that he was murdered, via suffocation, under orders from Richard. There was no action taken against the two junior Appellants, Mowbray and Bolingbroke, at this time, making their protest of the execution of Simon Burley at the Merciless Parliament seem like a very wise idea. For the faithful service they had provided against the Appellants, Richard rewarded a significant number of his close personal favorites with rich new titles which were to be sustained through lands that the Appellants had forfeited. Mowbray was created Duke of Norfolk; Bolingbroke Duke of Hereford; the king’s other cousin, the Earl of Rutland, Duke of Aumerle; the king’s half-brother, the Earl of Huntingdon, Duke of Exeter; and the king’s nephew, the Earl of Kent (son of the recently deceased half-brother of the king), Duke of Surrey, just to name a few. All in all, five dukes, four earls and one marquis were created by Richard. This was unprecedented and many chroniclers felt that it diminished the importance of the titles, even going so far as to name the group of newly created dukes the ‘duketti.’ The whole situation severely damaged Richard’s reputation with his subjects and he even felt the need to travel with a large body guard of Cheshire archers for the remainder of his realm.

The beginning of the end for Richard came when a quarrel erupted between the two younger Appellants, Mowbray and Bolingbroke. As in the situation surrounding Richard’s destruction of the three senior Appellants, the background behind the Mowbray/Bolingbroke feud is portrayed in several different manners by the chroniclers, but it appears that Mowbray had informed Bolingbroke that he believed that they were next in line to be prosecuted for their involvement with the Appellants. In addition, it was rumored that the king and his minister were planning to reverse the overturning of the attainder against Thomas, Earl of Lancaster (who had been executed for treason by Edward II in 1322), which would have absorbed the entire Duchy of Lancaster into the crown, ruining John of Gaunt and his heirs. Unexpectedly, Bolingbroke told all this information to his father, who then informed the king. Mowbray, in a panic, concocted an unsuccessful attempt to murder John of Gaunt and was promptly arrested. While Mowbray was in custody, Bolingbroke continued to levy accusations against him, including the murder of Gloucester. Richard, understandably, did not want this inquiry to proceed any further and it was agreed that the two men should engage in a jousting duel to settle their differences.

After months of preparation on both sides, the day of the fatal showdown had come. However, just when the two were about to begin their fight to the death, Richard stopped them from proceeding any further. Shortly after, it was announced that the two would be exiled: Mowbray for life and Bolingbroke for ten years. Exactly why Richard decided to go this route is not completely clear, but it would be naïve of one to believe that the exiles were not directly related to the men’s involvement with the Appellants. Before Bolingbroke departed England, Richard assured him that his inheritance would be secure if John of Gaunt should died while he was still in exile. When John did die, however, on February 3, 1399, Richard showed his appreciation for all his loyal years of service by extending Bolingbroke’s exile to life and simultaneously disinheriting him. This time, Richard had gone too far and all of England’s nobility was forced to worry if their rights would be taken away in the same fashion. The king’s blatant abuse of power would prove to be fatal.

Upon hearing of Richard deceitful enterprise, Bolingbroke, who was in exile in Paris, began planning to have his inheritance restored to him. With assistance from a number of powerful French lords, Bolingbroke was able to gather a small number of men, including the brother and son of the Earl of Arundel, in invade England. It is believed, at this point, that Bolinbroke had no intention of usurping the throne, only of regaining his inheritance of the Duchy of Lancaster. Meanwhile, Richard, thinking that his position was safe, made the mistake of journeying to Ireland to deal with his rebellious vassals, who were once again causing trouble. As guardian of the kingdom the king had left his one remaining uncle, Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, a man of mediocre military and political skills at best. After stowing himself and his followers on a shipping boat, Bolingbroke was able to land safely at Ravenspur in Yorkshire. Richard was informed of his cousin’s invasion but was slow in returning to defend his kingdom, giving Bolingbroke the opportunity to make some powerful allies, including the Earl of Northumberland and Hotspur and the Duke of York himself. Bolingbroke’s following only grew from then on and he moved to Bristol where he captured the king’s favorites Bussy, Green and the Earl of Wiltshire and had them beheaded.

Knowing of the defection of most of his friends, Richard was forced to wander through the rough terrain of Wales before arriving at Conway Castle. When Bolingbroke learned of his presence there, he sent the Earl of Northumberland to retrieve him. The earl was admitted into Richard’s presence and was received kindly, but he was most certainly not trusted by the king. Again, the chronicles vary as to what happened, but it appears that Northumberland informed the king that Bolingbroke merely wished to be restored to his rightful inheritance and for a select group of Richard’s favorites to be punished for their crimes. The king agreed to meet with Bolingbroke and left the safety of the castle, where he was promptly ambushed by Northumberland’s men, whom the earl had stationed out of view in order to trick the king. When Richard and his cousin me at Flint Castle, Bolingbroke greeted him with respect, but informed him that he had returned from exile to help him govern the realm more justly and effectively.

Bolingbroke then marched to London with his prisoner where the city readily submitted to him. It is believed that, by this point, Bolingbroke was fully intent on seizing the throne. One can only speculate as to why he changed his desire of being merely Duke of Lancaster to being King of England, but there are two reasons that seem fairly plausible: the positive reception Bolingbroke had received upon his return to England and the fact that he knew that, if Richard were to remain on the throne, there would be a good chance that he would exact revenge on him just as he had done on the senior Appellants just three years earlier. Therefore, Bolingbroke began to search for various methods of taking the throne for himself without appearing to be a tyrant. In the end, it was agreed that Richard should resign his crown because of misrule (as in the case of Edward III) and that Bolingbroke, as the closest heir in the male line, should succeed him. After having continuous pressure put on him, Richard finally agreed to resign the crown and Bolingbroke became King Henry IV on September 29, 1399, after being confirmed by parliament. Richard was reduced to the status of a mere knight.

With Henry now on the throne, Richard was moved to the more secure location of Pontefract Castle, a Lancastrian stronghold. The new king did not have to wait long to defend his throne as a plot was laid by the Earls of Salisbury, Huntingdon, Rutland and Kent, and Lord Despenser (all of whom were demoted by Henry IV, excepting Salisbury, from the higher titles they were given by Richard in 1397), to murder the king and his sons. Henry discovered the plot, most likely through his cousin Rutland (the only man involved not to face any sever repercussions) and the rebels were forced to scatter. All involved were ultimately captured and executed by common townspeople. The Earls’ Rebellion made King Henry realize that his throne would never be completely secure while Richard still lived. Therefore, orders were given for the former king’s death and by mid-February (most historians will give February 14, 1400 as the date), it was announced that Richard was dead at the age of thirty-three. It is difficult to conclude just how he died: Certain chroniclers claim he was attacked and murdered, while others maintain, more logically, that he was simply starved to death. The new king made sure to display Richard’s corpse at various places throughout the realm to assure his subjects that he was indeed deceased.

Assessment and Analysis

Richard II was very far from the man that his father, the Black Prince, and his grandfather, Edward III, were and this is made perfectly clear through his lack of enthusiasm for war and his inability to control his own magnates. On top of these facts, it was also wondered whether Richard was a homosexual since he never bore any children. When thinking of the reign of Richard II, it is difficult not to compare it with that of his great-grandfather, Edward II (another supposed homosexual). Like Edward, Richard had difficulty making decisions for himself and came to be dependent on a small group of favorites for advice, usually bad advice, to run the realm. Both men had to deal with a particularly powerful group of magnates who had no unifying factor (i.e. war with France or Scotland) to distract them. Edward lost his first favorite, Gaveston, when the Lords Ordainer had him executed, while Richard lost his first group of favorites when the Lords Appellant proceeded against them. Both men were able to bounce back from these experiences and exact revenge on their opponents. Edward did this after the Battle of Boroughbridge against Lancaster and Richard through his destruction of the Appellants in 1397.

Unfortunately, neither man learned their lessons and both cultivated new groups of favorites (Edward with the Despensers and Richard with Bussy, Bagot and Green, among others). This, combined with their tyrannical behavior, led to the same result for both men: deposition and death. It is true that Richard showed signs of being a genuinely good leader. His handling of the Peasants’ Revolt was nothing short of remarkable for a fourteen-year-old boy and the success he achieved on his 1394 expedition to Ireland was more than any English king had accomplished on the rebellious island for many years to come. Unfortunately, much of the success that Richard did enjoy (i.e. the peaceful period from 1389-1396) was due to the moderating force of his uncle, John of Gaunt. When John’s political influence waned, Richard turned tyrant; When John died, so did Richard’s reign.

In the end, Richard suffered the fate he did because he alienated his own people to the point where there was no turning back. The crushing of the Appellants was an instigator, but the seizure of John of Gaunt’s lands after his death was the final straw. It is interesting to wonder how Richard’s reign would have progressed had he not been disposed. It must be believed that he would have lived on in tyrannical and despotic fashion for another twenty or thirty years, or more, making Bolingbroke’s coup seem like a blessing. One final trait that Richard shared with his great-grandfather Edward II was that both men seemed to live on even after they died. Whereas rumors floated about that Edward II escaped and lived on for another fifteen years, there was actually a Richard lookalike, one Thomas Ward, who was used in future rebellions, namely that of the Percys, against Henry IV. In addition, the battle cry of “Richard is alive” was used for some time after the king’s death. The question of whether Richard’s deposition and death was the direct cause of the Wars of the Roses in the latter half of the fifteenth century is more a question to be asked in a biography of Henry IV. However, though the Plantagenets remained on England’s throne in the male line (through the houses of Lancaster and York) until their overthrow in 1485, the death of Richard marked the end of the direct line of the House of Anjou that had been on England’s throne since 1154, and therefore somewhat marked the end of an era in England.

References & Further Reading

Bennett, Michael. Richard II and the Revolution of 1399

Fletcher, Christopher. Richard II: Manhood, Youth, and Politics 1377-99

Hutchinson, Harold F. The Hollow Crown: A Life of Richard II

Mathew, Gervase. The Court of Richard II

Saul, Nigel. Richard II

Saul, Nigel. Three Richards: Richard I, Richard II and Richard III