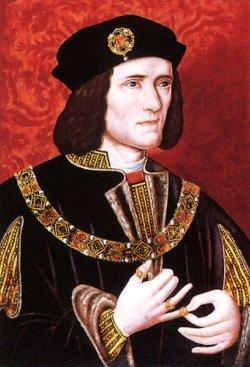

King Richard III

Born: October 2, 1452

Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire, England

Reign: June 22, 1483 - August 22, 1485 (2 years)

Died: August 22, 1485

Bosworth, Leicestershire, England (Age 32)

Biography

Richard Plantagenet was born the youngest child (and fourth surviving son) of Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, and his wife Cecily Neville on October 2, 1452. Very little is known of his early upbringing and he was, quite obviously, far too young to have any sort of involvement whatsoever in the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses at St. Albans in 1455. When tensions arose yet again between the Yorkists and Lancastrians, and the Yorkists were forced to flee the country in 1459, Richard and his younger brother George remained in England in their mother’s custody and the three undoubtedly had to keep a low profile while York, Edward of March and Edmund of Rutland (Richard’s other two elder brothers) and their allies were attainted in parliament. Though the Yorkists would return to England and gain back power for a short time, York was killed the following year at the Battle of Wakefield fighting the forces of Queen Margaret and Richard and George were temporarily sent to Burgundy for their own safety. They would not remain there for long though because their elder brother, Edward, had defeated the main Lancastrian army at Towton and taken the throne as King Edward IV. When Richard returned to England, he participated in his brother’s coronation ceremony and was created Duke of Gloucester (his brother George was also created Duke of Clarence) and made a Knight of the Garter at the age of nine.

During the first half of his reign, Edward IV struggled to find ways of supporting his youngest brother and most of the royal patronage went Richard’s elder brother, George of Clarence. Richard seems to have spent a great amount of time in the northern household of his cousin, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, the most powerful magnate in the realm (who also received a great amount of royal patronage) and the man who had been essential in gaining Edward IV the throne. Given this excess of royal patronage awarded to Warwick and Clarence, as opposed to the lack thereof given to Richard, some historians have found it perplexing that it was the former two men who rebelled against Edward IV in 1469, while Richard remained completely and utterly loyal to his brother. Once Edward IV had regained his freedom from the clutches of Warwick and Clarence (and made a purely-for-show reconciliation with the two), Richard was well-rewarded for his loyalty and was given a number of lands and appointments in Wales and northern England (many of which had been in the custody of Warwick or his family for generations). In addition, Richard was appointed as constable of England, a highly significant office, When Warwick and Clarence again rebelled (this time with French assistance) and chased Edward IV out of England, Richard accompanied his brother and a number of other faithful Yorkists into exile in the Low Countries, within the dominions of Duke Charles of Burgundy. There Richard and the Yorkists would remain for the next six months while Warwick ruled England in the name of Henry VI.

In the late winter of 1471, the Yorkists, with Burgundian assistance, invaded England so that Edward IV could reclaim his throne. The king, Richard and Clarence all met and reconciled their differences, making the Lancastrian position more precarious. After the Yorkists had retaken London and gained possession of Henry VI, Richard (now nineteen) played a major role in the Battles of Barnet (where Warwick was killed) and Tewksbury (where the house of Lancaster was virtually wiped out), which were to securely put Edward IV back on his throne. After the latter battle, Richard, as constable, was responsible for the execution of a number of Lancastrians in the Tewksbury marketplace. Certain chroniclers will claim that Richard was directly responsible for the subsequent murder of Henry VI in the tower, but this is most likely later Tudor loyalists who were intent on further tyrannizing Richard. If Richard had any involvement at all in Henry’s death, it most certainly would have been under direct orders from Edward IV himself. Whatever the case may be, the deaths of Warwick and Henry VI and his son (who had been killed at Tewksbury) placed the Yorkist regime firmly in control of affairs in England, in which they would remain until Edward IV’s premature death twelve years later.

Following the Yorkist success against the Lancastrians, Richard was held in high esteem by his brother the king and was given numerous grants of lands in the north, many of which had once belonged to Warwick, making him one of the wealthiest magnates in England and gaining him a substantial powerbase in the process. The only nobleman that was more powerful than Richard was his brother Clarence, which made it no surprise that the latter opposed his brother’s marriage to Anne Neville, the younger of the two daughters of Warwick and the widow of the late Prince Edward (the son of Henry VI), in 1472. Clarence had been married to Warwick’s elder daughter, Isabel, since 1469 and was looking for any way possible to disinherit both Anne and his mother-in-law, the dowager Countess of Warwick, the latter of whom Warwick had received munch of his land and his title from, shot ha the may enjoy the entire vast Warwick inheritance himself. Richard was the only man powerful enough to rescue Anne from Clarence (and most likely a life in a nunnery) and expected to receive his fair share of the Warwick inheritance. The quarrel raged on for quite some time before the king finally decided to completely disinherit Warwick’s widow and to split her inheritance evenly between Clarence and Richard. Though the king’s final decision may not have been the ideal situation for the feuding brothers, it most certainly helped to enrich both men, even if it meant destroying the life of the rightful heiress, showing that all three of the Yorkist brothers had at least a certain amount of greed and deceitfulness running through their veins.

Throughout the 1470s, Richard continued to gain power and influence and was a regular attendee of the royal council. He accompanied Edward IV on his “Great Enterprise” to France in 1475, apparently leading the largest contingent, and most likely played some sort of role in the downfall and execution of his brother Clarence in 1478. Whereas it is unlikely that Richard had gone out of his way to plot with the Woodville family (the relatives of the king’s wife) against Clarence, as some historians have hinted at, he certainly stood to gain from his downfall. When Clarence was finally executed, Richard was named chamberlain of England in his place, was given an additional number of Warwick’s former lands and his young son, Edward, was created Earl of Salisbury (a title formerly held by Clarence). For these reasons, it is unlikely that Richard would have had any major objections to Clarence’s execution, even if he did not play a prominent role in his downfall.

After Clarence’s execution, Richard increasingly distances himself from his brother’s court and indeed from the south of England in general. This gave him the opportunity to further build upon his dominating powerbase in the north, which would be so crucial to his eventual usurpation of the throne. These years leading up to the death of Edward IV were relatively quiet for Richard, with the exception of the brief war with Scotland of 1481-82 of which Richard became the leader of when Edward IV decided not to lead the English army in person. The Scots were undoubtedly instigated by Louis XI of France (their ally against the English), who was on bad terms with Edward IV at the time. Though Richard was able to win back the border town of Berwick from the Scots (who controlled it since it was handed to them by Queen Margaret in 1460), he was unable to bring the Scots onto the battlefield and was forced to deal with unreliable allies such as Alexander, Duke of Albany (brother of James III of Scotland), who had originally promised to aid the English in exchange for being place on the Scottish throne, but had ultimately defected back to his brother, and little else was accomplished before a truce was agreed to between the neighboring countries.

Events in England took a dramatic turn when Edward IV suddenly died, aged forty, on April 9, 1483 and was succeeded on the throne by his eldest son, Edward V, a boy of twelve. Since the final copy of Edward’s will does not survive, it is impossible to know exactly what his intentions were for the minority of his son and the events that followed his death are, to a certain extent, speculation. There were basically three different plans of action the government could take when an underage king ascended the throne: A regency could be set up which would give near sovereign power to one man until the king came of age (this was the case in the opening years of Henry III’s reign in the thirteenth century); A protectorate could be established in which a single man would be in charge of a council that would rule in the king’s name (this appears to be the role that Henry V intended for his brother, Humphrey of Gloucester, during the minority of Henry VI); or, the king could be officially crowned and the government would be run in his name by a series of councils until he came of age (which was the case during the minority of Richard II).

If Edward IV did in fact wish for a regency, or even a protectorate, to be established after his death (which a number of chroniclers claim he did), Richard, as the only living adult-male member of the house of York, would have been the logical, if not obvious, choice. However, the new king’s mother, Queen Elizabeth, and her relatives, the Woodville family, had other ideas and meant to have Edward V crowned as soon as possible so as to eliminate the need for a protectorate. They firmly established themselves in the royal council and ordered for the king to be brought to London, in the custody of Anthony, Earl Rivers (brother of Queen Elizabeth and the young king’s governor) with a large retinue. Richard, not wishing for a government dominated by the ambitious and hated Woodville clan in which he would be largely excluded (or even in danger), acted swiftly to gain possession of the king’s person. Earl Rivers did not seem to suspect any treachery was about to occur considering the fact that he met with Richard and his political ally Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, at Northampton so that they could all proceed together to Stony Stratford, where the king was lodged, and escort him to London. Richard then suddenly arrested and imprisoned Rivers and departed for Stony Stratford, where he also arrested the king’s half-brother, Richard Grey, and Sir Thomas Vaughan, the king’s treasurer, before gaining possession of the king himself. To justify his actions, Richard claimed that, in addition to the bad influence these men had been on Edward IV (leading him to a life of excessive decadence), they had conspired to murder him (Richard) and therefore could not be trusted. Upon hearing of Richard’s actions, the Woodvilles panicked. Queen Elizabeth took her numerous daughters and her younger son Richard, Duke of York, into sanctuary at Westminster Abbey for their own protection and most of the other Woodvilles, and Woodville supporters, fled the country knowing that their cause (which was never very popular in the first place) was lost.

This paved the way for Richard to march into London with the king. He then proceeded to have himself officially declared protector by the royal council, postponed the date of the king’s coronation from early May to late June and pressed the council to accede to the executions of Rivers, Grey and Vaughan as traitors against his person (the latter request was refused outright). As Richard then continued to consolidate his power and to push for the protectorate to be extended past the coronation, many historians have wondered whether or not he was yet planning to usurp the throne at this particular point and time. However, Richard’s subsequent actions from this point on swiftly dispelled any doubts of what his true intentions were. Firstly, he suddenly and without warning had William, Lord Hastings (one of Edward IV’s closest friends and a man who undoubtedly would have been against Richard’s usurpation), seized from a council meeting and promptly beheaded, claiming that he had been conspiring with Queen Elizabeth against him. Secondly, Richard persuaded the queen to release her younger son, York, from sanctuary, stating that it was only right that he should attend his own brother’s coronation ceremony, the date of which was rapidly approaching. Once Richard gained control of York, he promptly sent him to join his brother in the tower, where the latter had been lodged to await his coronation (which was the custom). Richard then had Rivers, Grey and Vaughan executed at Pontefract Castle without any real trial and without approval from the council. Finally, Richard ordered one Ralph Shaw, a Cambridge scholar, to put forward his (Richard’s) own claim to the throne, via a public sermon, in front of the people of London.

Though it is by no means clear as to how exactly Richard convinced the people to accept him as king, a number of chroniclers will claim that he bastardized the children of Edward IV by claiming that their father had been betrothed to another woman at the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, therefore making the union invalid. Others will claim that Richard bastardized Edward IV himself, stating that their mother, Cecily Neville (who was still alive at the time), had an illicit affair, resulting in Edward’s birth. Whatever the case may be, Richard was able to convince the council (to a certain extent through fear and intimidation) that he was the rightful King of England and was duly proclaimed so on June 26, 1483. He was crowned as King Richard III the following month. As for the sons of Edward IV, Edward V and the Duke of York, they were seen less and less within the tower until they were eventually not seen at all. To this day, it remains an obscure mystery as to what happened to the “princes in the tower,” which they appropriately came to be known as, but it would be incredibly difficult to disprove that they were not murdered under direct orders from Richard III in an attempt to further secure his own precarious hold on the throne.

Richard’s violent coup and the despicable actions that were inevitably part of it gained him few friends, particularly in the south of England, a region that never had any real reason to show the new king a great amount of love. It is therefore no surprise that shortly after Richard took the throne, a number of rebellions broke out in the south, involving a number of staunch Edwardian loyalists (who were undoubtedly shocked and appalled at what Richard had done to the sons of Edward IV), including several Woodvilles. After these rebellions had begun, a more surprising defection took place in the person of the Duke of Buckingham, the man who, just months earlier, had been Richard’s most powerful and enthusiastic supporter. It is by no means clear as to why Buckingham decided to rebel, given the fact that he was so lavishly rewarded by Richard for his services, but there are several theories that are plausible. One possibility is that Buckingham felt Richard was not acting swiftly enough in delivering him the Earldom of Herford (which had once belonged to his maternal ancestors) and the vast lands that went with it, though the king had promised on several occasions to do so. Another theory is that Buckingham, who was undoubtedly a highly ambitious man, had planned to put his own distant claim to the throne onto the table (after all, he was descended from both John of Gaunt and Thomas of Woodstock, the third and fifth surviving sons of Edward III respectively). It seems though, that the most likely situation was that Buckingham knew that, after the way he attained power, Richard’s regime would not last for very long and, as his staunchest supporter, he would unquestionably gone down with it.

Whatever Buckingham’s reasons may have been, the plan in the rebellion of 1483 seems to have been for the duke to attack from Wales with a large retinue as the king was dealing with the risings in the south. Once Richard was deprived of the throne, one Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, was to be put in his place and would then go on to marry Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV, to give his claim more substance. Tudor, who had been living in exile in Brittany since Edward IV took back the kingdom from Henry VI (Tudor’s uncle) in 1471, was the son of Margaret Beaufort, the sole remaining legitimate member of the house of Lancaster, and was therefore a shining beacon of hope for those opposed to Richard’s tyrannical rule. Unfortunately, this particular rebellion was destined to fail. Buckingham was never able to launch his attack from Wales due to unusually treacherous weather and, quite frankly, lack of morale from his primarily Welsh army. The duke was captured by Richard’s men and promptly executed. A number of other executions of rebel leaders followed and many of Richard’s loyal northerners became rich from the spoils left behind from the attainted rebel lords. Tudor, who had already departed for England, was forced to turn back when he was informed of Buckingham’s death in order to fight another day. Thought he rebellion was, in the interim, a complete failure, Richard now knew that he had an unpredictable enemy, with growing support within England, who could invade at any time and deprive him of his ill-gotten gains.

There is little that can be said about the reign of Richard III considering the fact that he basically spent the entire two years of it attempting (for the most part unsuccessfully) to establish himself on the throne while trying to justify the actions he had taken to achieve his dynastic ambitions, as well as, worrying about a potential invasion by Henry Tudor, which seemed increasingly likely after the events of 1483. Richard’s regime was put in an even more tenuous position when his only son and heir, Edward of Middleham, died in April 1484 at the age of eleven. The following year, Queen Anne passed away, giving rise to rumors that she was had been poisoned by the king so that he could be free to marry Elizabeth of York, his own niece (though these claims are mostly unsubstantiated). Richard did indeed make some sort of deal with Queen Elizabeth (Edward IV’s widow) to get her to drop her support of a marriage alliance between her daughter and Henry Tudor and also made entreaties to Duke Francis of Brittany to gain possession of Tudor. Unfortunately, Tudor and his band of followers were able to make their escape to France where they took refuge with King Charles VIII, before they would launch their fateful expedition to England in the summer of 1485.

Henry Tudor and his relatively small army of French, Breton and Scottish mercenaries, as well as a number of old Lancastrian loyalists, finally landed at Milford Haven in Wales in August 1485 and swiftly marched nearly two hundred miles before encountering the royal army. Though Richard was undoubtedly the better general (Tudor had indeed never fought in a battle in his life), the momentum seemed to be on the invader’s side. At the Battle of Bosworth, Richard was deserted by two major lords, the Earl of Northumberland and Tudor’s own stepfather, Lord Stanley, severely weakening his chances for victory. In the end, Richard decided to make one last desperate attempt to take out Tudor himself and came so close that he actually killed Sir William Brandon, Tudor’s standard-bearer. Unfortunately, Richard’s last dash effort proved futile and he soon after met his end (at the age of thirty-two) when he was unhorsed and savagely cut down. Tudor was proclaimed King Henry VII that day on the battlefield and Richard’s body was stripped naked and thrown out on the street, as if a piece of trash, to show everyone that the despot king was indeed dead. The move was a final insult to a man who had resulted to tyranny to win himself a crown. To this day, Richard has not received a proper burial, the only English king to suffer such a disgrace.

Assessment and Analysis

King Richard III is considered to be one of the biggest tyrants in England’s long and illustrious history. This reputation was only solidified by Tudor writers such as Sir Thomas More, William Shakespeare and basically every chroniclers of the era. It is no secret as to why Richard is remembered in such a negative light. After all, in his quest for the throne he mercilessly executed such honorable men as Earl Rivers, Thomas Vaughan and William Hastings without a trial or due cause. The worst crime by far though that Richard is credited with is the murder of his two young nephews, one of whom was his rightful king and the other the heir apparent. It is this atrocity that has gained him the hatred of most people who are even slightly familiar with his life and career.

But, did Richard actually kill the princes in the tower? It is true that Sir James Tyrrell, a staunch Ricardian supporter who has long been looked at as the princes’ murderer, confessed to the murder shortly before his own execution in 1502, but his confession was almost certainly obtained under duress from a man who thought he may have a chance of saving himself. Other scholars have suggested that the Duke of Buckingham or even Henry Tudor were responsible for the crime, while others still suggest that the princes were never murdered at all. Though it is fun to speculate on alternative outcomes to one of the biggest murder mysteries this world has ever seen, it would be bordering on naïve to conclude that Richard had no involvement in the highly convenient disappearance of the princes. It would be even more naïve to believe that the princes were not deceased when one looks at the fact that their mother, Queen Elizabeth, put her support behind Henry Tudor, a move she most certainly would not have contemplated if her sons were still breathing.

It was these political murders that Richard was forced to commit in order to gain himself the throne that have gained him his near-Satanic reputation and paved the way for accusing him of all kinds of atrocities that most likely have no basis except to further smear his name. For example, it is highly unlikely that Richard poisoned his wife Anne so that he could marry his niece, Elizabeth. It is proven that the queen had been ill for some time and Richard was certainly not foolish enough to take part in what have been such an unpopular marriage. Richard has also been accused of bringing about the downfall of his brother Clarence. Though Richard profited greatly from Clarence’s death, it is unlikely he would have pushed for it too hastily with the risk of damaging his own rising popularity at the time.

Finally, it must be analyzed as to what would make one look at Richard as anything less than a tyrant. After all, he did save England from yet another dangerous minority reign, which English (and especially Scottish) history had already proven to be wasp’s nests of civil discord. Furthermore, Richard saved the country from a government that would have been heavily run by the devastatingly unpopular Woodville family. Though Earl Rivers has always been regarded (even by Tudor historians) as a pious and sophisticated gentleman, Queen Elizabeth, her two sons from her first marriage and her brothers were nothing more than greedy opportunists who never should have been given any significant power. One must also consider that Richard was unswervingly loyal to his brother when he reigned as king and few contemporaries could have predicted his future actions, one of the primary reasons why he was able to pull off the usurpation. It is still, however, very difficult to discount all of Richard’s other despicable acts even if they did occur in a brutal age where one had to assert firm authority or be destroyed. The most likely explanation for Richard’s actions in 1483 were his desire to rid himself of the Woodvilles, who undoubtedly would have been hostile to him. Once he had committed all the atrocities he has become known for, he simply could not turn back and it is most likely at this point that his ambition took over and he decided to take the throne.

However history has treated Richard III almost all scholars will agree that his death at Bosworth was the end of an era. Not only was he the first English king to die in pitched battle since Harold II in 1066 (and the indeed the last English monarch to suffer that fate), Richard was the last monarch of the Plantagenet dynasty that had sat on England’s throne since the accession of Henry II in 1154 and is the epitome of a man brought down by his own vaulting ambition. No one had expected Richard to reign as king, being the fourth son of a man who never actually reigned as king himself and had only a controversial (if significant) claim to the throne and he was ultimately forced commit violent and treacherous acts to achieve his goals, eerily similar to King John’s supposed murder of his nephew, Arthur, back in the early thirteenth century. One might say that Richard was a man ultimately brought down by his own insecurity and paranoia. Most significantly though, Richard’s death is looked at by many historians as the unofficial end of the Middle Ages. Historic events that would occur in the reign of Richard’s successor, Henry VII, no doubt paved the way to the modern society we now live in.

Further Reading

Abbot, Jacob. The Life of King Richard III

Cheetham, The Life and Times of Richard III

Cunningham, Sean. Richard III: A Royal Enigma

Fields, Betram. Royal Blood: Richard III and the Mystery of the Princes

Hancock, Peter A. Richard III and the Murder in the Tower

Hipshon, David. Richard III

Hipshon, David. Richard III and the Death of Chivalry

Kendall, Paul Murray. Richard the Third

Peters, Elizabeth. The Murders of Richard III

Pollard, A. J. Richard III and the Princes in the Tower

Ross, Charles. Richard III

Saul, Nigel. Three Richards: Richard I, Richard II and Richard III

Seward, Demond. Richard III: England's Black Legend

Wilkinson, Josephine. Richard III: The Young King to Be